To be a linguist exploring an understudied language can often be lonely. Your life might revolve around a language that someone you meet at a bar wouldn't even know exists. One may thus resign oneself to being the only one in their everyday life interested in their favorite Cariban, Baltic, Omotic, Gyalrong or Gur language. But sometimes, it turns out that this isn't the case. For all you know, you may suddenly find yourself asked to teach a course about it, full of students for whom it is not obscure but relevant.

This is, perhaps, the dream of many an idle linguist. Yet it seems to have actually happened here at the Ohio State University. This semester, we are proud to be holding the second ever university class on Hawaiʻi Creole English, and the only class outside of Hawaiʻi itself, taught by our own Clint Awai-Jennings.

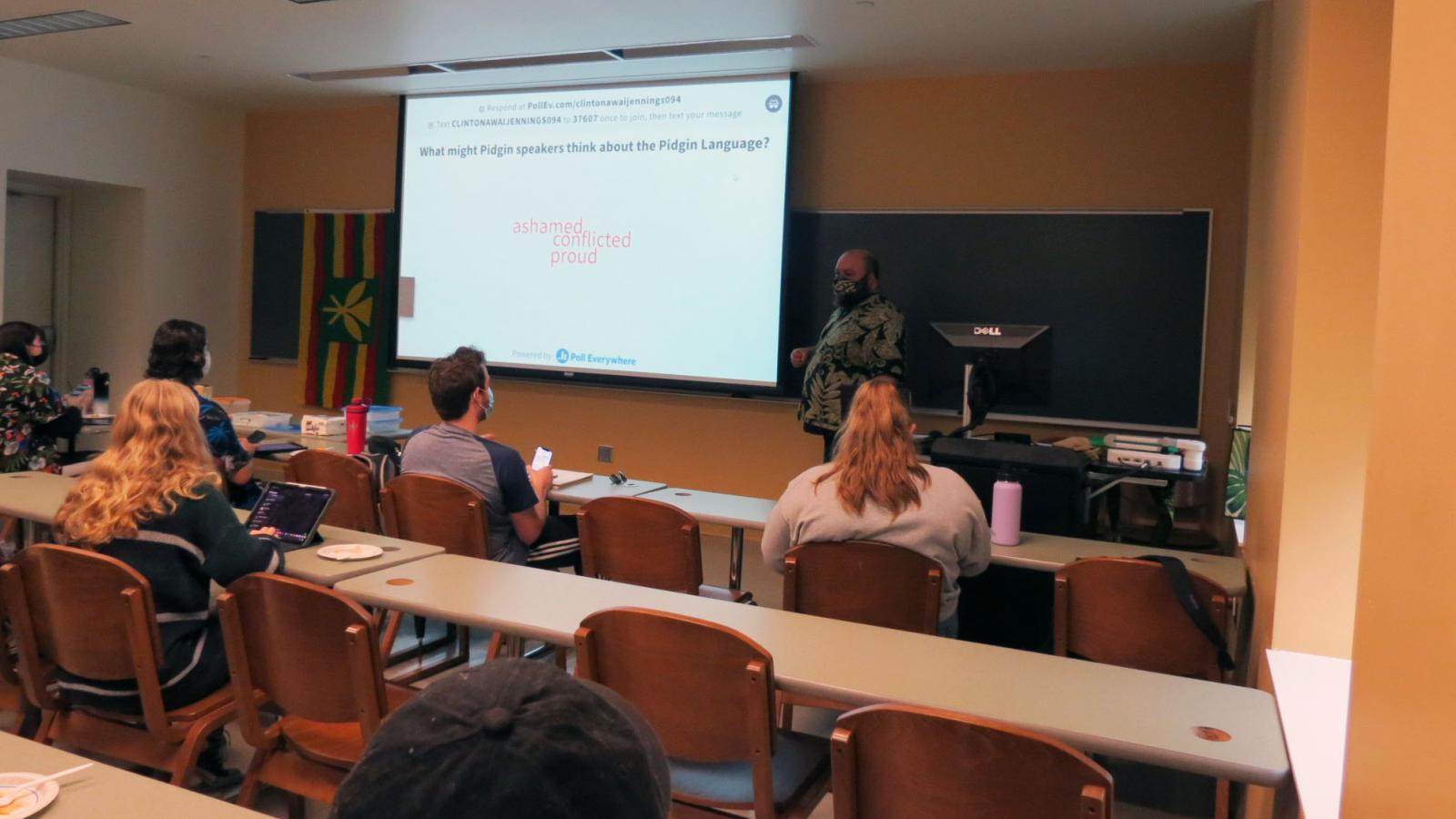

While perhaps less unknown than Tsez or Miskito, Hawaiʻi Creole English (or HCE) is commonly misunderstood even by its own speakers as not being a "real" language but instead a bastardized form of "bad" English, due to its particular sociolinguistic situation. HCE is however a full-fledged language with an elaborate grammar highly relevant for study of how new languages emerge in contact situations. Its language community, too, is identifiable, though its size unclear, with estimates centering around 600,000 native speakers in Hawaiʻi and 100,000 in the mainland.

HCE continues to be called Pidgin by its speakers, but while it did originate as a pidgin for interethnic communication, it stabilized in structure as it became a native language of second generation speakers between 1870 and 1920. Its origins lie in Hawaiʻi's economic history: first as a "middle stop" for Pacific fur trade after its 1778 "discovery" by Cook, a target of missionary activity, then a center for whaling and sugar plantations. The native Hawaiians were joined and soon outnumbered by incoming labor that spoke both Chinese (Cantonese and Hakka, from Southern China) and Portuguese (from the Atlantic islands of Madeira and the Azores).

The linguistic interaction of four socioeconomically distinct yet intertwined communities (natives, Chinese, Portuguese, Anglo-Americans) paralleled the formation of HCE, providing contact linguists with a case study in the nuanced interaction of not two but four languages. For example, HCE has stɛ (< "stay") as a locative and stative copula recalling Portuguese ficar, pau from Hawaiian pau as a completive aspect marker, and wan (= "one") as an article paralleling article usage in Cantonese, alongside features which appear to have arisen from HCE's internal dynamics. As such, HCE has featured critically in debates of creole genesis by theorists such as Bickerton and Siegel. Despite this significance, however, the socioeconomic and sociolinguistic realities have led to HCE being stigmatized as a language for only colloquial and not professional or literary usage, as well as decreolization and endangerment.

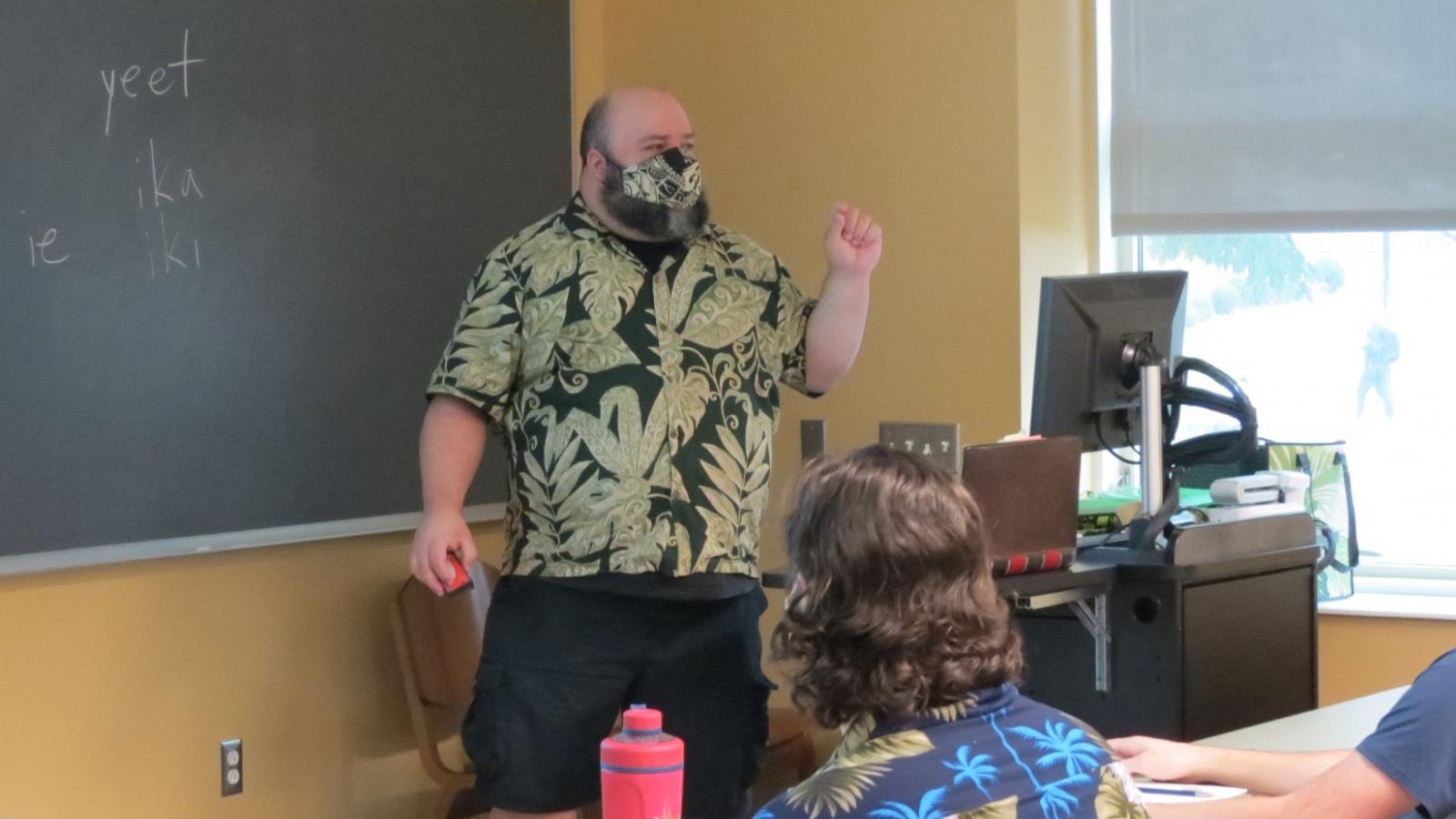

But at the Ohio State University, interest was such that demand from students led to Clint Awai-Jennings being asked to teach a class on his language of both heritage and research, the second ever university class on the Hawaiʻi Creole. Clint had previously taught Introduction to Linguistics, Language Evolution and Language Change, where he often recruited HCE, as a sample contact language, for the sociolinguistic concepts exemplified in Hawaiʻi, and because, Clint explained, "I'm also a very proud Hawaiian and enjoy sharing everything about the Hawaiian Islands."

While teachers of intro-level classes are happy to get students interested enough to further explore any linguistics, Clint's passion was contagious enough to draw students so much into Hawaiian linguistics that they requested a new class in it. "One of the things that drew students to the language is that it's new and different," Clint thinks. "Worldwide, contact languages are less frequently studied... The opportunity to intimately study a creole as well as the social issues of the Hawaiian Islands was not lost on them."

Assembling an entirely new class on an understudied language has not been without quite a bit of work. "There are basically zero teaching materials to pull from," Clint noted, "basically just a grammar book." But this open task was also an opportunity to tailor a class to the interests of its students. Clint built the class to focus both on the structure of Hawaiʻi Creole and its peculiar and dynamic sociolinguistic situation, where on one hand it is stigmatized to its own speakers as merely slang or "broken English'", but, on the other, Standard American English is also seen as "fancy", perhaps inappropriate for casual and intimate discourse. "I've had the fortune over the last few years, especially in this semester to share the culture, spread awareness of the linguistic ecology of the Hawaiian Islands," Clint said. "I hope to build upon this... and promote awareness back in the Islands."

The 31 students in the class "have been fantastic," Clint remarked, impressed by their enthusiasm and engagement. The level of engagement was striking also to Donald Winford, the current instructor of the department's ongoing seminar in contact linguistics, who noted that this engagement has enriched his own class as well. "Not a day goes by," he noted, "without mention of [material from] Clint's creole class". Perhaps it suffices to say that the department is yet again impressed by the passion for learning of our student body.